About the Galleries

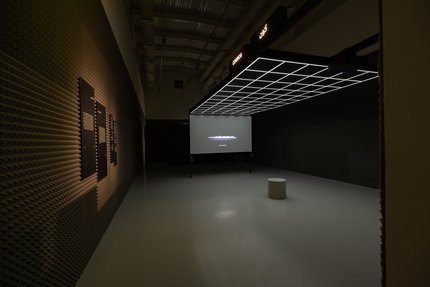

The Your Ghosts Are Mine: Expanded Cinemas, Amplified Voices original exhibition presents moving images that focus on contemporary experiences of community life, recollection, transnational crossings and exile. It offers an all-encompassing, immersive experience, through a selection of films produced, co-produced or initiated by Doha Film Institute, as well as video installations from the collections at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art and the future Art Mill Museum.

What kind of illusion does the desert embody? These stretches of sand and rocks, where the absence of landmarks prevail over the visible signs of civilisation, are places where time seems to stand still. Yet, paradoxically, aridity has enabled the preservation of some of the most archaic human traces in these areas, infusing them with a highly notable historical charge. Actually, nothing is less deadly than a desert, since everything lives longer there than elsewhere. In Arab literature, both sacred and secular, the desert is the place where something irreversible happens—going on a pilgrimage or wandering can result in an ordeal followed by a shattering revelation. It is a metaphysical space that contemporary cinema directors have made their own. The characters thus revealed, whether real (143 Sahara Street) or fictional (Land of Dreams), strive to survive there in adversity. Above all else, they are trying to see their dreams resist all forms of appropriation the world is subjected to—the desert being somehow protected from them thanks to its ontological hostility. These seem-to-be empty spaces allow genuine confrontation with oneself, sometimes to the point of confusion and madness (Abou Leila), as well as a confrontation with the infinite (Banel & Adama). The desert is where the tangible threat of a cataclysmic climatic future manifests itself unfiltered.

Ruins

LIDA ABDUL

Lida Abdul fled Afghanistan with her family following the Soviet invasion in 1979 and lived as refugee in India and Germany before immigrating to the United States. The artist’s work often focuses on bodies and landscapes, exploring their complex interaction as a way to examine notions of identity, homeland, exile, and political resistance. In this four-minute loop, Dome, Abdul documents her chance encounter with a young boy wandering a war-ravaged landscape. The boy stares transfixed at the blue sky through a roofless mosque while continually spinning in circles. The boy’s circling movements trace the shape of the roofless dome as he looks up at the sky, then comes the sinister throbbing of whirling rotor blades as a helicopter passes overhead.

WAEL SHAWKY

Wael Shawky’s work tackles notions of national, religious and artistic identity through film, performance and storytelling. Mixing truth and fiction, childlike wonder and spiritual doctrine, Shawky has staged epic recreations of the medieval clashes between Muslims and Christians in his trilogy of puppets and marionettes–titled Cabaret Crusade–while his three-part film, Al Araba Al Madfuna, uses child actors to recount poetic myths. The film is inspired by Shawky’s visit to the village of Al Araba Al Madfuna, built next to the archaeological site of a pharaonic kingdom in ancient Egypt. There, Shawky lived with its inhabitants for several weeks where he witnessed the community’s activities of digging underground to search for treasures, using metaphysics, alchemy and spiritual powers. In his film, children dressed in turbans and moustaches performing the roles of adults, explore the temple and speak the parables from Egyptian writer Mohamed Mustagab’s The Sunflower (1983). In this tale, the sunflower is a metaphor for inventing change, pointing out the duality of mythical and contemporary concerns.

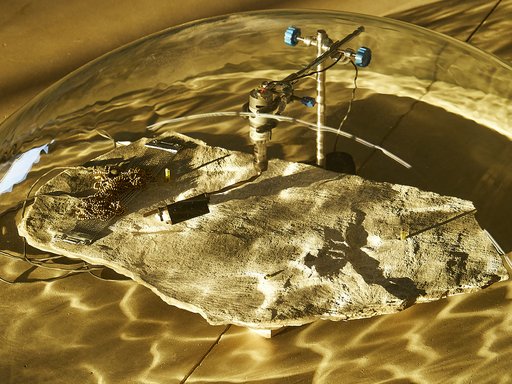

BASIM MAGDY

Shot in an arid landscape of extremes, My Father Looks For An Honest City (shot in Super 8, then transferred to HD video) is a re-enactment of Diogenes the Cynic’s philosophical statement of carrying a lit lamp in daytime, claiming to look for “an honest man”. Magdy filmed his own father while walking solitarily through a no man’s land, with petrified wood, unfinished buildings, and archaeological ruins, insignia of the new architectural prototypes of the New Cairo, a rising city on the outskirts of the ancient one. The re-enactment is set to the sound of a raging thunderstorm. Shooting on film, Magdy expounds the aesthetic possibilities of the medium by treating the film itself with a variety of household fluids, which dissolve the images in layers of color and add new details through stains and scratches, pushing the visual quality of the material beyond its actual source and into the unreal.

Fires

THE FLAME OF RESISTANCE

But what do these everlasting flames stand for? Flames from a vibrant hearth around which communities gather to rekindle the spark of revolution (A Riffle and a Bag)? Flames from a world doomed to total destruction by war (The Cave) or natural punishment (Monisme)? Flames from a world in the process of liberating itself, exploding and projecting all around an incandescence that dazzles anyone contemplating it (Mother I’m Suffocating)? Resistance without violence is impossible, and directors know that this inner fire they cherish is a pledge and a condition of their commitment. Additionally, some of these incendiary films do not hesitate to tell stories based on real facts, therefore introducing history into the perilous game of fiction: the immolation of a young Tunisian man in Sidi Bouzid, the very event which triggered the outburst of the 2010 Arab Spring, directly becomes the matric of Harka, whose narrative is symptomatic of a society on the verge of asphyxiation. Provoking both terror and admiration, fire is always in motion, and filmmakers never forget that it is in itself quintessentially cinematic.

Borders

ONE DAY THE WAR WILL BE OVER

What occurs when the horizon happens to run out? Women, men and children are forced to hide, to go underground, or to recreate artificial worlds made of puppets and miniature models. Films unsettled by war or social conflicts crystallise around the notion of microcosms. Filmmakers set out to conquer reduced, condensed, and confined territories, engaging cinema in specific staging choices. Consider the theatrical treatment of the prison reenactment in Ghost Hunting or of the Morocco-European border in Ceuta’s Gate: as in a laboratory experiment, the locations are characterised by abstract scenic elements (lines on the ground), to focus primarily on what is at stake between each side—or rather on what is no longer at stake in these human communities dominated by the reign of fear. Prisons and borders, as well as shantytowns, are forbidden spaces where filming is not authorised, and yet, where the most inventive filmmakers refuse the curse of the missing image choosing, instead, to create original displays with powerful testimonial ambition.

Exile

WHERE IS MY HOUSE?

Photos: Wadha Al Mesalam, courtesy of Qatar Museums ©2025

Is the exile of filmmakers a source of cultural transfer and hybridisation? What do we keep from our home country? For that, you still need to have a country, as director Elia Suleiman reminds us so accurately: “I have no homeland. And since exile is the other side of having a homeland, I do not consider myself to be in exile. On the contrary, and at a certain level that is not political, I could say that each place embodies both homeland and exile”¹. The dialectic of exile, embraced by filmmakers born in Palestine, Syria or Kenya, generates a third cinematic space-time, which is neither the country of birth nor the country (chosen or not) of one’s daily life, but an entanglement of the two, where multiple intimate, familial, social and linguistic perspectives get mingled. Exploring exile through documentary or semi-documentary narration is a way of fighting amnesia as well as a certain mythologisation of integration promoted by official discourses. Here, filmmakers give time to unofficial narratives, made up of fragments and shifts, whether through portraits (Faya Dayi) or self-portraits (Chasing the Dazzling Light). It is never a lost paradise that they seek to find again—for being exiled prevents one from believing in any utopia but leads instead to trusting displacement as a possible creative decentring.

Deliverance

WHERE THE HEARTS OPEN

What do viewers really know about these women honoured by independent cinema? The stories of their lives are interwoven with heroism and the quest for independence. But they are also portraits of what they are not or struggle to become. In any case, whether the metamorphosis is flamboyant or the obstacle is painful, these women from Turkey, Libya, Morocco, Iran, Algeria, Cambodia and Egypt never submit to their destiny like slaves. On the contrary, they subject the film to the explosive power of their existential crisis. Facing the camera or escaping it, sideways or in voice-over, they are always filmed grappling with the complexity, even the ambivalence, of their feelings and movements. These committed women drive, swim, run, talk and demonstrate, in cinematographic proposals occasionally tinged with oneirism, ready to transcend their carnal envelope to compose unique and unconventional movements, ultimate volte-faces against the rigidity of the patriarchal world.

Fantasma

GHOST IMAGES

Isn’t cinema the most accurate medium for ghosts? The ghosts of night, vibrating with its disquieting strangeness? The ghosts of a buried or inaccessible past? The ghosts of a nebulous future or a tortured unconscious? Not forgetting the immaterial ghosts of cinema itself, those existing only on 35mm-film or in pixels, revealed by projections on canvas or superimposed on a city’s walls? For many filmmakers and artists, questioning the history of their country (be it Syria or Lebanon) begins with questioning the images produced there and that are disseminated in both active or shut-down cinemas. Precious archival footages, sometimes threatened with disappearance, that need to be tamed or even recomposed through new editing. Vernacular, fragmented, crossed-out, and incomplete images, giving a voice to people who are no longer there in the flesh, but whom the camera has immortalised forever—simultaneously dead and alive. This cinema en abyme is transgressive because it shows us how to cross the threshold that separates the representation of the world from its fantasma.

Dance

HASSAN KHAN

Hassan Khan’s work confronts common life circumstances with intimate, confidential experiences, generating a form that gives rise to imaginary communities. This form also poses fundamental questions, seduces and repels, combats expectations, induces mystery and helps re-articulate our experiences with shifting power structures. Khan makes use of a wide range of media, including video, photography, performance and installation. The artist sees each medium not as a domain to be mastered, but rather as a field of possibility, potential and learning. Jewel opens with flashing lights gradually transforming into the form of an anglerfish accompanied by original music, created by the artist, informed and developed out of the shaabi genre; an urban music form with roots in the Egyptian popular classes. This mesmerising loop is the simple depiction of two men dancing. It is a restaging of a scene the artist encountered on a street in Cairo. On a summer evening in 2006, Khan was in a taxi when, out of the corner of his eye, he saw two men dancing on a crowded street. That scene, only glimpsed, formed a vivid mental image.

Cosmos

THE LAST FRONTIER

Photos: Wadha Al Mesalam, courtesy of Qatar Museums ©2025

What if exploring the world also involved venturing into its last frontier: the cosmos? Lately we have witnessed a surprising proliferation of science-fiction films not only from Palestine and Lebanon, but also from Thailand. Until very recently, the cosmos was the only space that was not colonised, the only space on which to project a utopian land: not an allegory of post-colonialism but of anti- colonialism. Based on real events (The Lebanese Rocket Society) or on purely imaginary computer-generated visions (In the Future), these films do not hesitate to take a detour via the Universe to question contemporary societies, human challenges, science’s morality, as well as urgent political issues such as segregation and occupation. With these directors, the genre’s conventions have been forever disrupted, not only to make audiences dream but also to push them to reflect on their own humanity.

Futurism

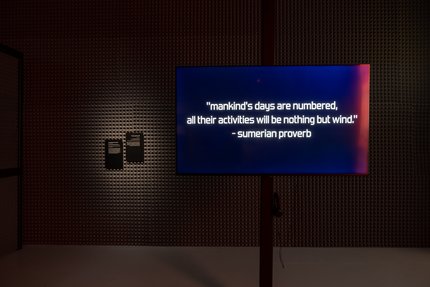

SOPHIA AL MARIA

Photos: Wadha Al Mesalam, courtesy of Qatar Museums ©2025

The seemingly disparate sources of inspiration for Sophia Al Maria’s multidisciplinary practice include pop culture, anime, Arabic poetry, sci-fi, and her personal experience of pollution and climate change. Working primarily with film and narrative text, the artist weaves captivating tales as a way to process her thoughts and feelings about the future, particularly in the current extinction climate. Her recent work focuses increasingly on the isolation of individuals via technology, consumerism as proxy religion, and how agency and chance play in the blinding approach of an uncertain future. Along with friend and musician Fatima Al Qadiri, Al Maria coined the concept of “Gulf Futurism”. In Sad Sack, a recently published collection of writings, Al Maria explores the possibility that, in some respects, the Gulf is already living within the future imagined by those in the West. She investigates the various ways in which this future is not evenly distributed or that it is simply misunderstood, particularly with regard to feminism.