Biography

Bahman Mohassess was an Iranian visual artist, translator, and theatre director. Born in Rasht, the capital of northern Iran’s Gilan Province, Mohassess traced his origins patrilineally to the Mughal Dynasty and matrilineally to the Qajar Dynasty. He was the cousin of artist Ardeshir Mohassess (1938–2008). At the tender age of 14, Mohassess painted landscapes of his native Rasht as an apprentice to painter Seyyed Mohammed Habib Mohammedi, who had trained at the Russian Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. After completing apprenticeship, Mohassess enrolled but did not complete his studies at Tehran University’s Faculty of Fine Arts (today referred to as the College of Fine Arts) in 1950, followed by the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome in 1954. Other Iranian painters who studied in Italy during this period include Behjat Sadr (1924–2009) and Mohsen Vaziri Moghaddam (1924–2018). In Rome, Mohassess frequented the studios of Ferruccio Ferrazzi and the Francesco Bruno Foundry, under the direction of Arturo Bruni.

Mohassess is regarded as an Iranian cultural icon and was commissioned to produce sculptures for public squares throughout Tehran under the patronage of the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Empress Farah Diba. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, several of his public sculptures were removed or destroyed, the nudity prevalent throughout his oeuvre has frequently been censored, and his sexuality, which artist Nicky Nodjoumi (1942–) believes impacted his work, has not been officially addressed in his home country. Despite this, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (hereafter, TMoCA) exhibited works from its permanent collection by Mohassess and Francis Bacon in 2017. The works exhibited at TMoCA included still lives or figures without explicit content. Works deemed “sensitive” are held in the museum’s permanent collection but have never been publicly exhibited after the revolution. Mohassess’s relationship with his native Iran remained tense and complex throughout his lifetime.

While in Tehran in the 1950s, Mohassess became a crucial figure in the country’s avant-garde artistic and literary scene. He was part of the Anjoman-e honari-ye Khorus jangi (Fighting Rooster Art Society), also referred to as the Sureʽālist-ha-ye Khorus jangi (Fighting Rooster Surrealists) an artistic movement established by Jalil Ziapour (1920–1999) and others in 1948. The art society fostered collaborations between poets, painters, writers, and critics in several of the society’s journals. It was the leading representative of the Cubist artistic language in Iran, promoting a connection between political commitment and creative expression. Scholar Aida Foroutan believes that in the 1950s, Mohassess and other members of the art society displayed surrealist tendencies in their unique practices. Mohassess served as an editor of the society’s literary and artistic weekly publication, Panjeh-ye Khorus (Rooster’s Foot), regarded as a radical modernist journal. In Tehran, Mohassess developed a close relationship with Nima Yushij (1895–1960), who was dubbed the Pedar-e sheʽr-e now (Father of New Poetry), and befriended the likes of poet and painter Sohrab Sepehri (1928–1980), poet Hushang Irani (1925–1973), and writer Gholam Hossein Gharib (1923–2004), who went on to define Iran’s progressive artistic and literary movements of the mid-20th century.

After the American and British-backed military coup to overthrow the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953, Iran witnessed mass protests and an exodus of artists and intellectuals, including Mohassess, who left Iran for Italy in 1954. Throughout the next few decades, Mohassess would participate in numerous exhibitions and biennials throughout the globe, translate Italian authors such as Italo Calvino and Curzio Malaparte and French writers such as Eugène Ionesco and Jean Genet into Persian, and continue to work on commissions — making frequent, brief trips to Iran. As a theatre director, he staged Ionesco’s Les Chaises in 1966 and Pirandello’s Henri IV in 1968 in Tehran. Referring to Iran in the 1960s, Mohassess stated that his problem with the country was not the government, but rather the people’s behavior, which led to his permanent move to Italy at the end of the decade. Mohassess ultimately died in obscurity, believed to have been dead for decades before the documentary of the director and writer Mitra Farahani titled Fifi Howls from Happiness, which captured the final months of the artist’s life and his on-camera death in 2010. In both Farahani’s documentary and Ahmad Farouqi Qajar’s Cheshmi ke mishenavad (The Eye That Hears) from 1967, Mohassess considered death a “performance” and noted that an artist’s death was as important as their entrance into the artistic scene.

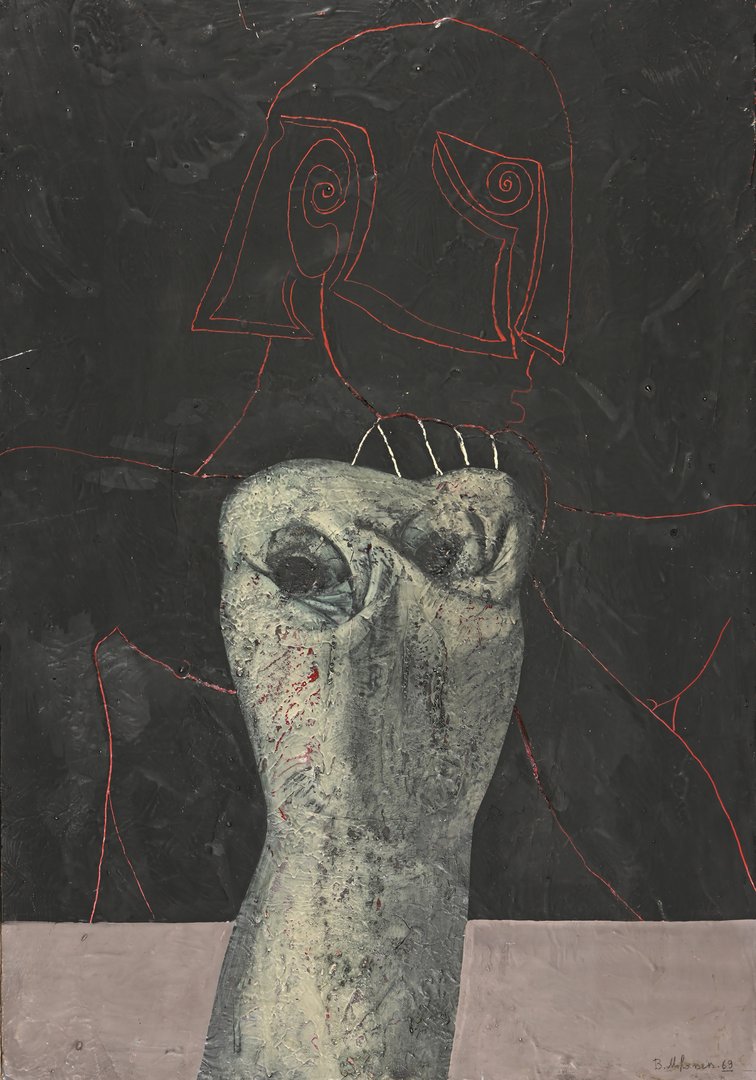

In Farouqi Qajar’s documentary on Mohassess, the artist recalled his conversation with the painter Charles Hossein Zenderoudi. Mohassess found that painting was a necessity, a habit, and a part of his physicality, thereby becoming a necessity that relieved him. He often stated that in art, it was not the material that was important but the expression. Mohassess’s work, which includes painting, sculpture, and collage, has frequently portrayed his strife and his compassionate views on a so-called cruel world, humanity’s primal nature, as well as global political turmoil, commenting on disasters such as oil spills, the assassination of American Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., the Gulf War, or the nuclear accident of Chornobyl, to name a few. Mohassess often felt that through his work, he was “preaching alone […] in a desert” and would “make no difference.”

The subjects of his paintings are often depicted in grey, stone-like tones, lacking hands, feet, mouths, or eyes, yet maintaining a human-like form. Mohassess stated that this was representative of the “condemnation of humanity,” which had begun as multidimensional but was no longer. To express this absence of dynamism, Mohassess intentionally amputated the limbs and removed the facial features of his subjects.

His work has often been defined as erotic, frequently featuring nude imagery. The most common motifs in his oeuvre include the fish and the minotaur. The fish is believed to convey dark symbolism; often depicted out of the water, the fish represents the artist’s alienation. While many have associated the minotaur’s masculinity with Mohassess’s sexuality, he described it as “a being apart” that is both “extremely beautiful and in this beauty inhabits the darkness of its being.” His style has frequently been compared to Western counterparts, such as Max Ernst, Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, Francis Bacon, and Pablo Picasso; he is commonly referred to by the Eurocentric label “Persian Picasso.”

Mohassess never desired to leave a legacy, nor did he wish for his works to be left for sale. As a result, he often destroyed his work. Despite this, Mohassess has been collected by figures such as Nelson Rockefeller and major international institutions, including the TMoCA, Jahan Nama Museum in Niavaran Palace, Pasargad Bank, Tate Modern, and the Barjeel Art Foundation.