Biography

Hamed Abdalla hailed from a family of Egyptian peasants who migrated to Cairo in the early 20th century and settled in the district of Manial Al Rodah. The young boy was accustomed to helping his parents work on the soil, and this deep connection to the land would resonate throughout his life and work.

Abdalla attended a nearby Quranic school. When it came time to apply to universities, he enrolled at the School of Applied Arts in the department of wrought iron. His time there was marked by clashes with his professors, which resulted in his expulsion. He decided to apply to the School of Fine Arts, seeking a more compatible education, but was denied entry.

Abdalla’s earliest paintings can be traced to the mid-1930s when the regulars of a café served as his first models. In 1938, Abdalla exhibited a selection of his paintings at the Salon du Caire, where he extended an invitation to his subjects, essentially treating them as guests of honour. With this initial revelation of his work, Abdalla presented himself as an artist and a champion of ordinary people.

1941, Abdalla held his first solo exhibition at Horus Gallery in Cairo. At the Salon du Caire of 1941, Abdalla and Tahia Halim (1919– 2003) crossed paths. Despite the stark disparities in their socio-economic background, this artistic duo discovered a shared passion. They established the Atelier Abdalla in 1942 in downtown Cairo. Over the following two years, Abdalla continued showcasing his work in various exhibitions in Cairo, Alexandria, Ismailia, Port Said, and Port Tawfik.

In 1945, Abdalla and Halim married, and in 1949, the couple decided to relocate to Paris. During those years, Abdalla experimented with the Arabic letter, as demonstrated by a 1947 “self-portrait” in which he used his first name to depict a face. Until the end of his life, Abdalla entertained the endless possibilities of the Arabic language, both in its spoken and visual forms.

Abdalla was invited to participate in the Égypte-France exhibition hosted by the Pavillon de Marsan at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1949, and in 1950 held a decisive exhibition at Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. In 1951, Halim interrupted her studies and went back to Cairo. Her marriage to Abdalla had grown increasingly complex, and their divorce was officialised in 1957.

Between 1953 and 1955, Abdalla embarked on a series of paintings entitled Sham El-Nessim, which were met with great success. They were executed on crystal by Steuben Glass in New York. They were featured in a collective exhibition entitled Asian Artists in Crystal, which travelled between 1956 and 1958.

Abdalla’s studio operated until 1956, during which time he travelled between Europe and Egypt. Before his final departure, he held a momentous retrospective exhibition titled Egypt, Crossroads of Civilizations at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Cairo.

In October 1956, due to the Tripartite Aggression, and despite his reservations about the Egyptian regime, Abdalla adamantly refused to live in or exhibit his work in nations at war with Egypt. He had married Kirsten Blach (1932–2022), a Danish nurse, and they decided to self-exile in Denmark. Abdalla quickly adapted to his new home, exhibiting his work and opening another studio in Copenhagen.

In 1957, Abdalla held an exhibition entitled L’Egitto di Abdalla in Palermo. The location ultimately profoundly impacted the artist; the harmony created by the fusion of the different cultures appealed to his sense of unity and connection, drawing attention to European roots in Arabic and Muslim heritage.

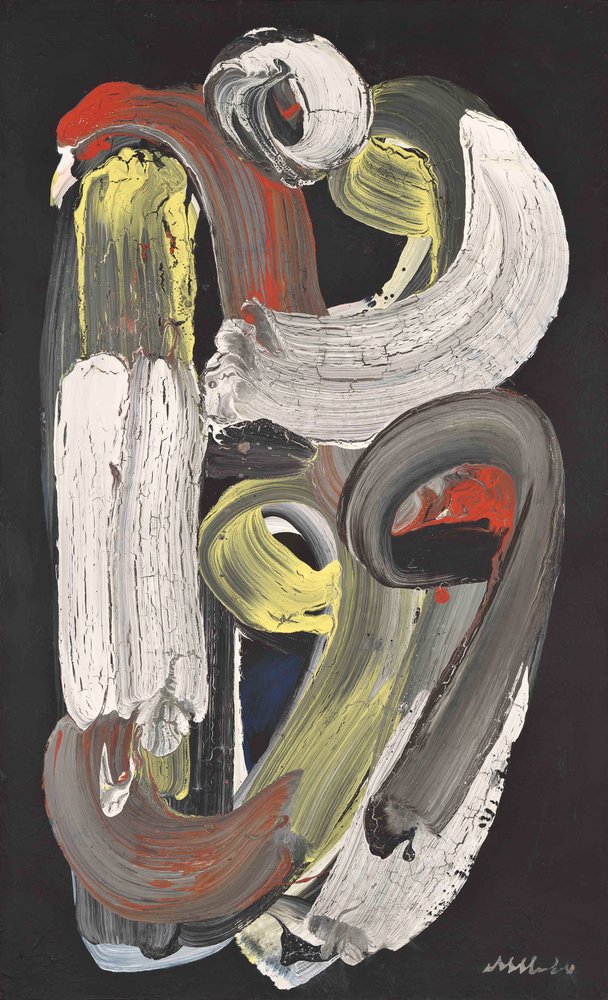

Beginning in 1958, the artist drew on his knowledge of calligraphy to depict images that he dubbed mots-formes (word-forms), ‘anthropomorphic words’, or ‘expressionist lettrism’. The decade spent in Copenhagen was fruitful; Abdalla exhibited across the country and in touring exhibitions across Europe, the United States, and Asia. Denmark also connected Abdalla to the CoBrA movement, artists such as Herbert Gentry (1919–2003), and groups such as Decembristerne and Den Anonyme.

Despite his success, Abdalla and his wife decided to leave Denmark as Abdalla felt isolated from his Arab peers. He had established himself as a central figure in Paris for resident and transient Arabs, and he moved back in 1966. With the Arab-Israeli War of 1967, Abdalla’s defence of the Palestinian cause was very much against the European political climate, and he severed all ties with art dealers in France due to their support of Israel.

Unable to find exhibition spaces in Europe and seeking to amplify his position on the Palestinian cause, Abdalla returned to exhibiting in the Middle East. Simultaneously, he denounced the incompetent dictatorships in the Arab world. In 1967, Abdalla held a retrospective at the National Museum in Damascus, Syria. In 1968, Abdalla exhibited for the first time in Beirut in an exhibition entitled Le Verbe 1957-1967 at Gallery One.

In the 1960s, he began creating anthropomorphic shapes out of letters. Abdalla’s talismanic period revealed an artist of even greater subtlety who would morph shapes and forms and make his magical writing system. This new alphabet also became an expression of a political stance.

In the mid-1970s, Abdalla returned to painting subjects inspired by nature, with collections such as Ahl Al Kahf (The Legend of the Seven Sleepers, or Companions of the Cave), using both Biblical and Quranic references, and another collection inspired by caves and natural formations, in what is known as his convulsions period.

Abdalla held more exhibitions in the 1970s and 1980s. Demonstrating his paramount support for the cause, Abdalla donated all the paintings remaining from the 1968 Gallery One exhibition to a prospective International Solidarity Museum in Palestine. The museum was bombed during the Lebanese Civil War, and the paintings have been lost to sight since then, but this donation of 119 paintings and 30 graphic works is the largest ever made to the museum for Palestine.

Abdalla passed away in Paris on 31 December 1985.